Specialized in Object and Library & Archive Conservation

Ejagham Skin Covered Mask

Report Summary

Owner: Bryn Mawr College

Accession #: for WUDPAC - ACP 1805 for Bryn Mawr - 99.3.79

Object: Skin covered cap mask

Artist/Maker: Possibly Ejagham peoples

Object Date: 19th - 20th Century

Materials: wood, animal skin, animal horn, metal pins

Dimensions: 57 x 73 x 20 cm

Consulted: Lara Kaplan: Objects Conservator and Affiliated Assistant Professor, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library and the University of Delaware

Marianne Weldon: Objects Conservator and Collections Manager for Art and Artifact Collections, Bryn Mawr College

Kathy Gillis: Elizabeth Terry Seaks Senior Furniture Conservator and Affiliated Assistant Professor, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library and the University of Delaware

Report Date: 05/06/2021

Treatment Images

Historical Context

The attribution to the Ejagham people played a role in focusing my research further within this style of masks, often referred to as “cap masks”. Skin covered cap masks with a specific styling of horn like coiffure hair designs were thought to have originated in the Ejagham regions of the Cross-River Region in the late 19th century. These cap masks are often associated with female coming of age ceremonies, funerary rituals, and the masquerade practices of Ikem. Much of the research around skin covered masks does not focus on one cultural group or region. Groups other than Ejagham discussed with skin covered mask practices are the Anyang, Bangwa, Banyang, Ekoi (which sometimes the Ejagham are referred to as), Ikem, Mbube, Nsikpe, Widekum, and throughout parts of Ibibioland. Because of the extensive cultural exchange and the overlap of location terminology with cultural groups, attributing a mask to a certain cultural group or place becomes very challenging without direct input from Cross-River Region members. Due to this ambiguity, take all group attributions of skin covered masks with a grain of salt.

Through visual examination, anthropological studies, and technical analysis of Cross-River region cap masks there is considerable information available on the mask materiality. The heads are carved from wood, usually a soft wood for ease of carving. The hair (often horn shaped, but can take on other forms as well) can be carved from wood, or constructed with plant fiber, animal hair, or human hair. The wooden hair is attached via mortise and tenon joins, or stuck in as pegs. This particular object has animal horns for hair, which seems unusual. It is almost certain the horns are replacements, and the original hair material is unknown. The horns are secured using a peg that attaches to the head and the inside of the horn, as they are hollow. The skin is often animal, specifically duiker, antelope, or sheep. Oils are sometimes applied to the skin. The teeth can be carved in relief or carved separately and affixed to the mouth. When carved separately the potential materials are wood, bone, ivory, metal, or teeth from animals. The eyes are often carved in relief but are sometimes covered with metal. The mask decorations can be dyes and pigments constructed from tree bark, plant saps, fruit and leaf extracts potentially with a proteinaceous binder. The material identification is somewhat limited here as these plants are often described with their local names and not their scientific names, making it difficult for non-locals to identify the specific type of plant. Symbols and decorations can be applied via pigment, or dye, or are carved into the mask.

See full report for citations and sources.

Condition and Description

The object is a three-dimensional human head shaped mask carved out of wood that is covered in animal skin held in place by metal pins. The bottom of the neck flares out into an ovular base. The pins holding the skin in place are located in the center of the ears, around the nose, around the base of the mask, and along the proper right (PR) side of the mask. The skin covering the mask is various shades of brown. The eyes and mouth of the mask are carved in relief in the wooden base and left exposed through strategically placed gaps in the skin. The eyes are closed and the mouth has thin lips with bared teeth. The ears and nose are covered in the skin. There are eleven holes drilled into the skin and wooden base at the bottom of the mask to accommodate an attachment of woven plant material (now missing) to help fasten the mask to its accompanying garb. There are three horns attached to the head, two long spiral shaped horns on the sides and a shorter, arched horn on the top. Each horn has black textile wrapped around the base of the horn, where it is attached to the head. There are 5 hash marks on the top of the PR horn.

Overall, the object is in stable condition, and if handled carefully and kept in a suitable environment, any degradation that occurs will be negligible. The proper left (PL) and top horns are not securely attached to the head. The PL horn seems looser than the top horn. There are tears in the skin on the outer side of each eye, and on the back of the head, and all seem fairly stable. The edges of the tears are bright, suggesting they happened relatively recently, but all seem stable. There are holes of various sizes in the animal skin that expose the wooden base underneath the skin. It is unclear if the holes resulted from manufacture, or appeared later, but none are recent. There are abrasions on the skin covering the nose and on the forehead below the top horn. The skin has a darker coloration around the mouth, eyes, top of the head, front of the base, and back of the base. The skin has a lighter coloration on the center of the back of the head and back of the neck. The lighter coloration is likely from wear on the surface of the skin, revealing parts of the corium layer underneath. The cause of the darker coloration is still unknown and could be from materials applied to the skin surface, wear, or handling.

Ethical Considerations

Spiritual Repercussions:

Upon researching this object, the possibility of ceremonial importance was very evident. I wanted to make sure this treatment did not impede on that ceremonial importance or potential spiritual energy the object holds and/or gives off. Through my research and consultation with African studies scholars I know of no spiritual repercussions of treating this object using the steps and methods outlined in the proposal. This does not mean there are no repercussions. It simply means that through the research and scholarly channels I had access to, I did not learn of any.

Research Limitations:

Keith Nicklin’s research was the main source of information for the historical context section of this report, and for me to understand the context of this object. I retain a healthy skepticism for all of Nicklin’s claims as I am wary of accepting information about an African culture from one white man due to all of the misconceptions and falsehoods attributed to African people by white men that stem from colonialism. I wish I had the time and ability to access more authors on the subject in order to vary the perspective from which I am receiving information, even if that perspective ended up being from a handful of white men instead of one.

Centering the Cross-River Region:

Even though there seemed to be no spiritual repercussions, I still wanted to center the Cross-River Region community in this project as best as I could. In crafting my technical study, I tried to approach studying this object in a manner that would not only benefit my learning, and the institutional owner of the object, but the community from where it potentially came. I say potentially because as I learn more about this object it becomes less likely that it was used in Ngbe ceremony. This very well could be an object crafted for tourist trade or for Westerners studying anthropology in the Cross-River Region. However, I still want my research to benefit the Cross River Region in some way, even though these skin covered masks seem to be a thing of the past. I hope my research and analysis of this object will be helpful in documenting the history of skin covered masks, therefore documenting a part of history about the Cross-River Region.

I would also like to state without knowing specifically what the Cross River region (especially the Ejagham group) community members would want in terms of care, handling, and treatment of this object, I treated and handled this object with care to the best of my ability. I acknowledge that the steps I have taken may not be the steps the Cross River community would have recommended or wanted for the object.

Treatment Summary

Surface Cleaning

The first pass was with a soft bristle brush and a HEPA filter vacuum. The second pass was with cosmetic sponges. The horns exhibited substantially more surface dirt than the skin.

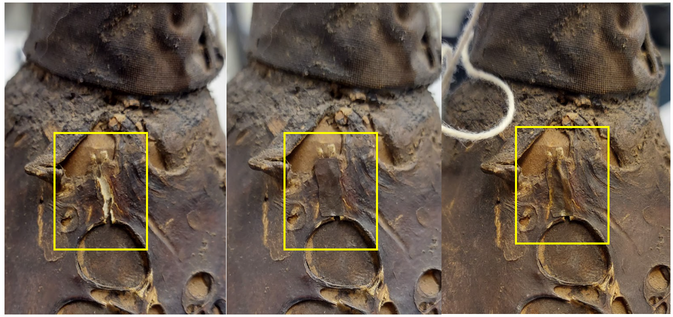

Mending & Inpainting

I toned a lightweight kozo fiber paper using Golden fluid acrylics. The toned paper was coated with Lascaux 498HV to be solvent reactivated with isopropanol when applied to the skin. I inpainted the mends further once applied to improve aesthetic integration.

Technical Study

This object was also the subject of the technical study I performed for WUDPAC science coursework. The objective of the study was material identification of the horns, skin, potential skin coatings, and wood that compose the cap mask. The image below shows a brief summary of the results. For more details, check out the RESEARCH page or CLICK HERE.